The future of cybersecurity lies not in more complex systems but in better integration between human psychology and technical solutions. By designing security solutions that work with human nature rather than against it, organisations can build more resilient networks.

A harried employee clicks a convincing phishing email. A tired system administrator misconfigures a firewall rule. A frustrated developer creates a workaround that bypasses security protocols.

These everyday scenarios lead to the majority of security breaches—not sophisticated zero-day exploits or advanced persistent threats. As organizations invest heavily in security technology, many continue to design systems that expect humans to behave flawlessly, despite overwhelming evidence that they won't.

Understanding the human element of enterprise security

In my years working with organizations on security implementation, I've observed a fundamental truth: when team members make rushed decisions under pressure, something usually goes wrong—both for individuals themselves and for their organizations. Security systems that ignore human psychology or expect people to adapt perfectly to rigid controls will inevitably create vulnerabilities.

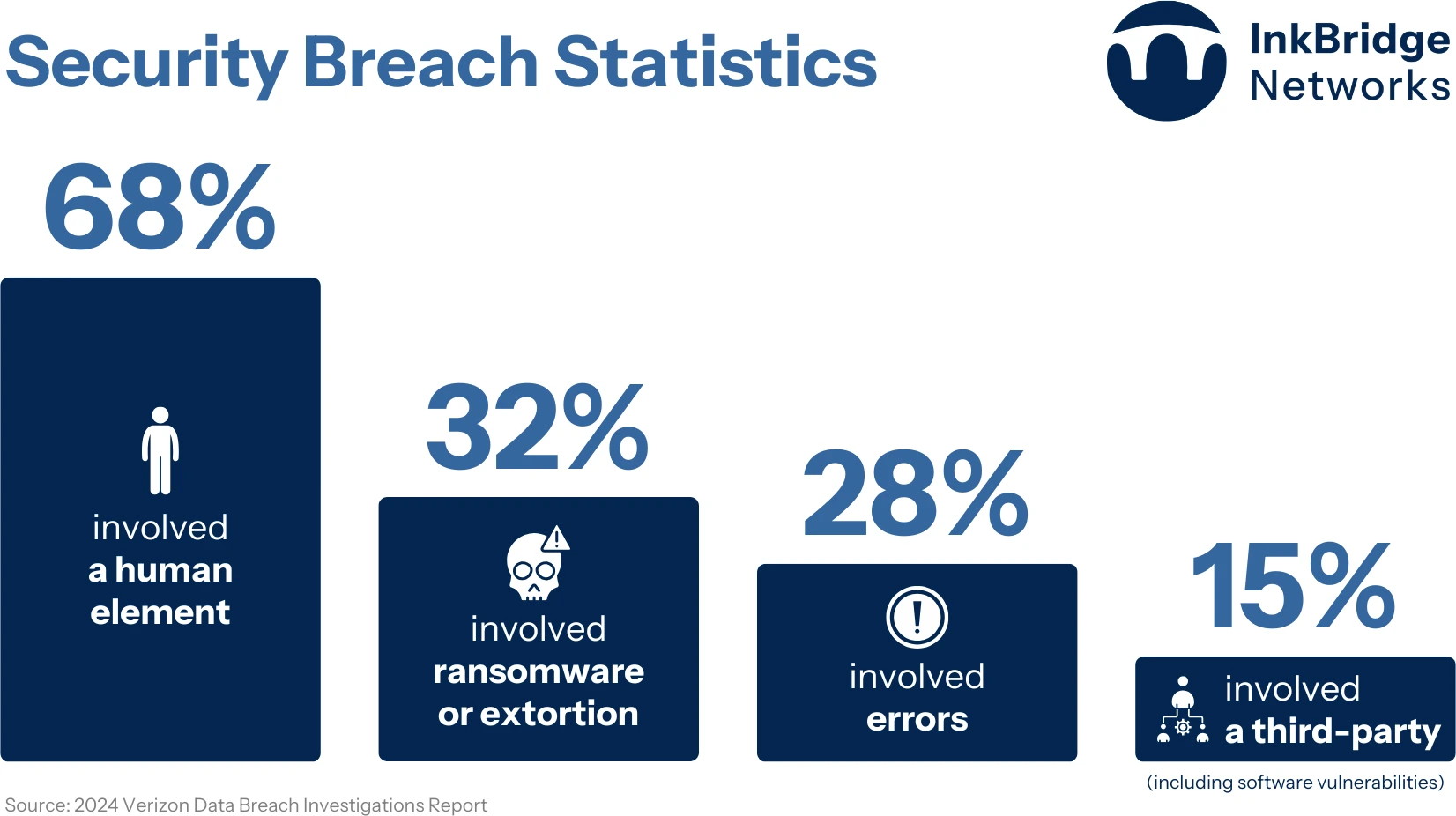

The 2024 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report found the human element was a component in 68% of breaches last year. This statistic serves as an alarming call to action for a different approach to security.

From the 2024 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report

From the 2024 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report

Two driving forces in modern security

Over the past few years, two complementary philosophies have emerged to address this challenge:

- Security by design: This approach involves integrating security measures from the beginning of development rather than retrofitting them later. Security considerations become foundational elements of services, protocols, and systems rather than afterthoughts.

- Human-centred security: This approach recognizes that organizations must trust their staff to do their jobs with vigilance. The challenge is creating an environment where that trust is supported by systems designed for human success rather than setting people up for failure.

Why traditional security approaches fall short

Many organizations rely heavily on security checklists and rigid compliance frameworks. While these provide necessary structure, they often create a false sense of security when implemented without deeper understanding.

For example, security professionals sometimes focus intently on checking the box for security data in transit while neglecting data security in storage. The result? They leave their organization open to a security breach that could expose millions of records containing sensitive data. This mentality creates dangerous blind spots in risk assessment.

The problem isn’t with checklists themselves—structured documentation remains valuable—but with how organizations implement them. Without understanding the underlying principles and context behind security strategies and requirements, teams simply check boxes without addressing substantive vulnerabilities.

What does a human-centred approach mean?

A human-centred approach means understanding that people are imperfect and designing security solutions with that admission in mind.

The best way to increase human-centred security is to empower people to understand their job. They need to grasp how their work fits into the bigger picture and develop a deep appreciation for the technologies they use. Individuals who understand context make fewer mistakes and better decisions.

Empowerment also means equipping people with the right training, tools, and time required to do the job well, without needing to cut corners. When professionals have what they need and can feel personally satisfied with the results they produce, they will see security as a valuable aspect of their role. They can embrace security as an integral part of creative and engineering processes, and as a fundamental quality attribute of their work.

In contrast, harried employees are more likely to see security as an additional burden—something to be minimised, delegated to the IT security department, or even ignored entirely.

The human-centred approach requires acknowledging some fundamental truths about human psychology:

- People have limited attention spans—especially when it comes to security. When considering cognitive priorities, security often receives a tiny portion of a user’s mental bandwidth. Their primary job responsibilities, personal concerns, and immediate tasks naturally take precedence. Security measures that demand excessive cognitive load will be circumvented or ignored.

- Support issues primarily stem from human factors. When security problems arise, they typically originate from someone not following procedure or making an understandable mistake. Rather than assigning all the blame to an individual, effective security leaders admit that security problems are a problem of the system. Security leaders use these mistakes to re-evaluate processes and to improve documentation. They also develop tools to both catch issues before they become a problem, and to give people more information so that they can make better choices.

- Workplace culture influences security behaviour. In some organizational cultures, employees find it difficult to deliver bad news up the management chain. This communication barrier can mask serious security vulnerabilities, as when networks need investment, but budget constraints prevent open discussion of the issues. Other organizations encourage good communication but have a “fly by night” attitude where corners are cut and mistakes are not just expected, but which are also condoned.

Building effective human-centred security

Based on extensive experience implementing security across diverse organizations, these key elements form the foundation of an effective human-centred security approach:

1. Take a holistic view of security

Security assessments must examine the entire environment when implementing solutions. This comprehensive perspective sometimes means declining to deploy certain technologies if they would create more vulnerabilities than they solve within the existing infrastructure.

When implementing access control and other security measures, consider how they integrate into your overall operation, not just as isolated components protecting specific assets.

2. Design systems that complement human nature

Secure systems should accommodate human limitations rather than expecting flawless performance. This means creating intuitive interfaces, reasonable processes, and multiple layers of protection to catch inevitable human error.

Security tools should give users enough information to make informed decisions and understand appropriate actions. This approach reduces support questions over time, as users develop the ability to identify issues and problem-solve on their own.

3. Provide comprehensive information and context

One of the most effective security approaches involves providing detailed documentation and contextual information. When people understand not just what to do but why certain measures exist, they make better security decisions.

Systems should offer monitoring capabilities, comprehensive documentation, and information about specific configuration elements. That way, users are empowered to identify and resolve issues independently, reducing dependency on outside support.

4. Transform incidents into improvement opportunities

Every security incident presents a valuable opportunity to enhance processes. Security teams should consistently re-evaluate procedures after support issues to identify ways to improve documentation, tooling, and training.

The goal should be to automate actions where possible: scripts and tools can stop their work if they run into issues. A tired administrator might instead miss a critical error message and keep working! Tools can also be written to better summarize information and give administrators critical information which they can use to perform root cause analysis.

Tools are good for automation, but it is difficult to create tools which make the correct decision. In contrast, people are poor at automation but are good at making decisions based on complex or incomplete information. Play to each strength!

This continuous improvement cycle helps security teams anticipate and prevent similar issues while staying ahead of evolving threats.

Real-world application: balanced approaches to security

Consider the debate around authentication protocols like PAP versus CHAP. Many security checklists forbid the use of clear-text passwords, and push organizations away from Password Authentication Protocol (PAP) toward Challenge Handshake Authentication Protocol (CHAP).

This oversimplified approach overlooks a crucial trade-off: while CHAP protects passwords in transit, it requires storing them in clear text in databases. Security leaders must ask themselves which scenario presents a greater risk—someone intercepting network traffic during the brief login moment, or attackers breaching a database containing millions of accounts? The statistical evidence overwhelmingly points to database breaches as the more common and much more damaging threat.

This example illustrates how human-centred security requires understanding real-world risk rather than following generic best practices that might inadvertently create more significant vulnerabilities.

Building a culture of security

The most successful security implementations share several common traits:

- Documented processes that enable informed decisions. While checklists alone prove insufficient, well-designed documentation empowers team members to understand security requirements and exercise appropriate judgment when unexpected situations arise.

- Clear communication channels. Create environments where people feel comfortable reporting issues and asking questions without fear of blame. Security teams should facilitate this open communication to address vulnerabilities before they become critical.

- Realistic expectations. Security systems should be designed with the understanding that users will make mistakes and prioritize their primary job functions over security measures. Anticipating these realities leads to more effective controls.

- Continuous improvement cycles. Each security incident offers an opportunity to refine how systems accommodate human factors. Organizations that learn from these experiences gradually develop more resilient security postures by addressing root causes rather than symptoms.

Looking toward comprehensive security

The most effective protection against threats like phishing attacks, credential compromise, and insider threats isn't just better technology—it's technology designed with human behaviour in mind. These vulnerabilities exploit predictable human tendencies: our trust in apparent authority, our tendency to reuse passwords, and our occasional lapses in judgment.

After decades in security, I've learned that systems which acknowledge human limitations ultimately prove more resilient than those demanding perfection. By embracing human-centred security, we transform our defensive posture from fragmented technical controls into a cohesive strategy that works with human nature.

The question isn't whether your organization will face human error—it's whether your security infrastructure is designed to anticipate and contain it. When you build systems that expect and accommodate human behaviour, you will reduce incidents and create an environment where security and productivity reinforce each other.

The most secure organizations are the ones that have learned to make security work for humans, not despite them.

Need help?

At InkBridge Networks, we've spent decades helping educational institutions build resilient, secure campus networks that balance academic freedom with robust protection. Our team includes engineers who have implemented AAA solutions for some of the world's largest university systems and contributed to the protocols that power global academic networks like eduroam. If your institution is facing network challenges or planning infrastructure updates, explore our solutions for educational institutions or request a quote for your specific needs.

Related Articles

Big Tech Concentration Made CrowdStrike Update a Catastrophe

As we dissect the CrowdStrike outage, we’ll find the human error was multiplied by the concentration in Big Tech, says network security expert Alan DeKok of InkBridge Networks.

Exposed: National Public Data breach makes a nation’s secrets public

The hacking of 270 million social security numbers from National Public Data reinforces the best practice for personal data: always encrypt PII. The cat is out of the bag for National Public Data. In mid-August, the data aggregator officially confirmed a huge data breach, although the cybersecurity community had inklings of the incident months earlier, in April.